In Syria, Humanity and Heritage Suffer War's Irreparable Devastation

to fly off to Damascus, Syria.

Looking back a decade later, the two brief months I spent in Syria—which I wrote about extensively on this blog—stand out in my mind as some of the happiest of my life, and among the most formative. I spent my weekdays absorbed in Arabic study, advancing swiftly thanks to the patient Syrians all around me. Each weekend, I explored a different part of the country, clambering over ancient ruins, wandering unknown souks, and revelling in Syrians' warm hospitality.

The place wasn't without its frustrations, to be sure—and the political tensions were palpable—but I came away from that summer with a deep reverence and respect for the country, its people, and its heritage.

Today, those fond memories make it that much harder to watch the destruction that is being heaped upon that same country, those same people, and that same heritage. The Syria I fell in love with no longer exists, and will never again exist as such.

The scale of the destruction wrought by the ongoing civil war defies comprehension. Since 2011, when the initially peaceful revolution devolved into a chaotic melee, over 200,000 Syrians have been killed, many of them civilians. Some 4 million have fled abroad, mostly to refugee camps in nearby Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey. Nearly 8 million more have been displaced within the country's borders. Out of a population of 22 million, less than half still live in their own homes. (Source.)

The one Syrian I have stayed in touch with is my former teacher Boshra, who thankfully now lives outside Syria, and has thus been spared the tragic fates of many of her compatriots. Millions who stayed were not so lucky. (These include even Father Paolo, the gentle Italian priest who ran the monastery of Deir Mar Musa; he disappeared in 2013.)

I often wonder what became of the other Syrians I knew. Is Ra'ife, the old Christian woman who rented her downstairs rooms to me and other foreign students in Damascus, still alive? What about Mahmud, the young Kurdish boy who guided me around the now-flattened souks of Aleppo? And Maher and Walid, the university security guards who gleefully joined our class in playing charades all through that endless bus ride to Palmyra? What of the fruit vendors I befriended on a long weekend in Hama? Or Mohamed, the t-shirt seller who spent long hours sharing tea with me, trying so earnestly (though unsuccessfully) to convert me to Islam? And where is Mr. H, the (not-so-secret) secret police agent who kept an eye on the foreign university students? Was he killed in the uprising's first days? Or has he continued participating in the regime's crimes against its people? Or did he refuse to take part in the horror, and instead flee abroad with his family?

What of the dozens of kind-hearted Syrians who offered a bottle of water, an impromptu Arabic grammar lesson, a hunk of bread, or a free lift to a curious young American student one summer, ten long years ago?

As the news from Syria has grown darker with each passing month and year, my mind has kept returning to these questions, hoping perhaps to make sense of the staggering chaos by breaking it down into comprehensible, personal bits. But without answers, these questions provide little comfort or understanding.

Still searching for a connection, I often reflect on the damage being wrought upon Syria's historical sites, which I explored with such exuberance that summer. The grand Aleppo mosque I visited has been bombed, and its minaret toppled. Aleppo's world-renowned souks are rubble. Battles have raged in the ruins at Bosra, the Crusader castles of Krak des Chevaliers and Qala'at Salah Eddin, and the streets I walked in so many cities and towns. The Islamic State has captured Palmyra and reportedly rigged its sweeping Roman ruins with explosives; after standing for over two millennia, the city's days now look numbered.

UNESCO World Heritage administrators and Syrian museum caretakers are doing what little they can to limit the war's damage, but heartbreaking before-and-after photos and other media coverage continue to catalog mounting losses to a cultural heritage that was once among the world's richest. Many of the world's greatest civilizations—ancient Egypt, the Greeks, the Romans, the Assyrians, Babylon and the first Muslim empires, the Ottomans—left behind architectural and cultural wonders here. Syria is home to some of the world's oldest cities, and is the birthplace of writing. The war risks erasing in just a few short years what it took humanity millennia to build.

To lament the destruction of Syria's cultural heritage is not to ignore the suffering of its people. These are the twin tragedies unfolding from this war, and while the human suffering is of far greater and more urgent concern, the losses to Syria's heritage are not unimportant. This was the case after the 1982 massacre in Hama—one of the world's first glimpses of the brutality of which the Assads are capable—as one resident recently described in a moving account:

Shared symbols are essential for the building of a nation. (What would America be without Mount Rushmore, the Lincoln Memorial, the Golden Gate Bridge, or the Statue of Liberty?) With so many of Syria's symbolic sites in shambles and museums looted, the task of building a new national identity for this New Syria will be that much more challenging.

The physical destruction also represents a blow to the global community, whose cultures owe so much to Syria, but who will have to settle for visiting a New Syria whose cultural offerings are, at best, diminished, and more likely devastated. The New Syria will have far less to offer tourists than the old—a significant blow to a country that will need tremendous sums to rebuild.

The historical sites that symbolize Syria's long and storied heritage will bear the scars of this war forever, like memorials to the emotional scars borne by the survivors. The crumbled walls, gaping mortar blows, and bullet holes in the ancient stones will serve as permanent, tangible monuments to this modern war's destruction, and to whatever lessons we might someday take away from it.

Next: An upcoming blog entry will focus on the struggle to find ways to help from afar.

Looking back a decade later, the two brief months I spent in Syria—which I wrote about extensively on this blog—stand out in my mind as some of the happiest of my life, and among the most formative. I spent my weekdays absorbed in Arabic study, advancing swiftly thanks to the patient Syrians all around me. Each weekend, I explored a different part of the country, clambering over ancient ruins, wandering unknown souks, and revelling in Syrians' warm hospitality.

The place wasn't without its frustrations, to be sure—and the political tensions were palpable—but I came away from that summer with a deep reverence and respect for the country, its people, and its heritage.

Today, those fond memories make it that much harder to watch the destruction that is being heaped upon that same country, those same people, and that same heritage. The Syria I fell in love with no longer exists, and will never again exist as such.

|

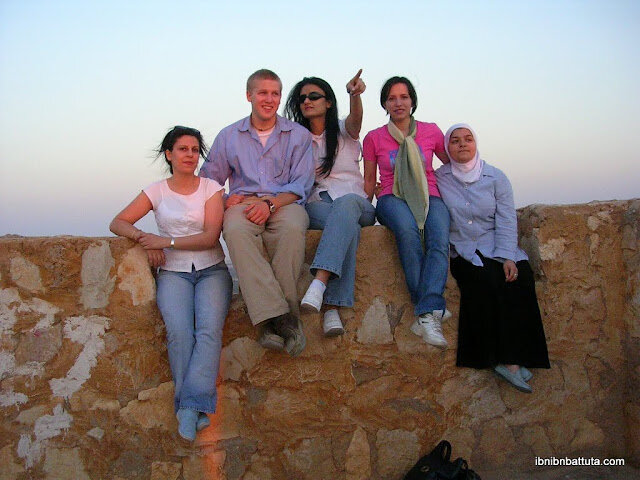

| Ten years ago, Syria was a tranquil, isolated, and culturally rich country full of people eager to exchange with outsiders—the perfect place to spend a few months studying Arabic. |

The one Syrian I have stayed in touch with is my former teacher Boshra, who thankfully now lives outside Syria, and has thus been spared the tragic fates of many of her compatriots. Millions who stayed were not so lucky. (These include even Father Paolo, the gentle Italian priest who ran the monastery of Deir Mar Musa; he disappeared in 2013.)

I often wonder what became of the other Syrians I knew. Is Ra'ife, the old Christian woman who rented her downstairs rooms to me and other foreign students in Damascus, still alive? What about Mahmud, the young Kurdish boy who guided me around the now-flattened souks of Aleppo? And Maher and Walid, the university security guards who gleefully joined our class in playing charades all through that endless bus ride to Palmyra? What of the fruit vendors I befriended on a long weekend in Hama? Or Mohamed, the t-shirt seller who spent long hours sharing tea with me, trying so earnestly (though unsuccessfully) to convert me to Islam? And where is Mr. H, the (not-so-secret) secret police agent who kept an eye on the foreign university students? Was he killed in the uprising's first days? Or has he continued participating in the regime's crimes against its people? Or did he refuse to take part in the horror, and instead flee abroad with his family?

What of the dozens of kind-hearted Syrians who offered a bottle of water, an impromptu Arabic grammar lesson, a hunk of bread, or a free lift to a curious young American student one summer, ten long years ago?

|

| A gang at the local fruit market in Hama who were overjoyed to meet a young American traveler. Where are they now? |

Still searching for a connection, I often reflect on the damage being wrought upon Syria's historical sites, which I explored with such exuberance that summer. The grand Aleppo mosque I visited has been bombed, and its minaret toppled. Aleppo's world-renowned souks are rubble. Battles have raged in the ruins at Bosra, the Crusader castles of Krak des Chevaliers and Qala'at Salah Eddin, and the streets I walked in so many cities and towns. The Islamic State has captured Palmyra and reportedly rigged its sweeping Roman ruins with explosives; after standing for over two millennia, the city's days now look numbered.

UNESCO World Heritage administrators and Syrian museum caretakers are doing what little they can to limit the war's damage, but heartbreaking before-and-after photos and other media coverage continue to catalog mounting losses to a cultural heritage that was once among the world's richest. Many of the world's greatest civilizations—ancient Egypt, the Greeks, the Romans, the Assyrians, Babylon and the first Muslim empires, the Ottomans—left behind architectural and cultural wonders here. Syria is home to some of the world's oldest cities, and is the birthplace of writing. The war risks erasing in just a few short years what it took humanity millennia to build.

|

| At left, my 2005 photo of the bust of 10th-century poet and philosopher Al-Ma'arri, located in his hometown of Ma'arrat al-Nu'man. At right, the same bust, beheaded in 2013 by Islamist fighters. (Photo source.) Al-Ma'arri's controversial views on religion have long drawn extremists' ire; the war gave them the chance to act upon it. |

"We knew that the human loss was too massive to bear, but the destruction of historical Hama left a wound which would never heal. Even the subsequent twelve years I spent in Assad's hellish detention camps did not overshadow the loss of Hama. I visited Hama numerous times after my release but could not reconcile that loss."Someday (soon, we must hope) Syrians will emerge from this conflict into a New Syria. When they do, they will have reason to lament both the catastrophic loss of life and the destruction of the country's material heritage. The war will have robbed future generations not only of grandparents, aunts and uncles, and older siblings, but also of the magnificent creations of all those who came before them. Those creations, after all, are symbols of the nation. Ottoman palaces, Assyrian idols, Roman ruins, and ancient synagogues, churches, and mosques all testify to the rich diversity of modern Syria. (Indeed, this is why they are a target of extremists seeking to homogenize the country's pluralistic culture.)

Shared symbols are essential for the building of a nation. (What would America be without Mount Rushmore, the Lincoln Memorial, the Golden Gate Bridge, or the Statue of Liberty?) With so many of Syria's symbolic sites in shambles and museums looted, the task of building a new national identity for this New Syria will be that much more challenging.

The physical destruction also represents a blow to the global community, whose cultures owe so much to Syria, but who will have to settle for visiting a New Syria whose cultural offerings are, at best, diminished, and more likely devastated. The New Syria will have far less to offer tourists than the old—a significant blow to a country that will need tremendous sums to rebuild.

The historical sites that symbolize Syria's long and storied heritage will bear the scars of this war forever, like memorials to the emotional scars borne by the survivors. The crumbled walls, gaping mortar blows, and bullet holes in the ancient stones will serve as permanent, tangible monuments to this modern war's destruction, and to whatever lessons we might someday take away from it.

Next: An upcoming blog entry will focus on the struggle to find ways to help from afar.